Abstract

This is a huge topic that one could write a book about (and I'm sure multiple people have). There are many gunsmiths, manufacturing centres and styles of weapons to talk about and I'm not even going to try to do that. What I am going to try to do is trace the history of the matchlock in the Holy Roman Empire in broad terms. I will begin with the fist hand cannon with a simple swivelling, 'Z' shaped, match holding serpentine lever nailed to its wooden stick-stock and end with fully stocked mechanically linked matchlock and snap matchlock arquebuses of the early 16th century. For this purpose I have chosen to trace the development of the stock and lockwork in separately since these two features seem to have evolved somewhat independently of each other. Also, there is no discussing stock and matchlock evolution without including some discussion of hand cannon. There are guns which are quite primitive hand cannon that have some semblance of a mechanical lock and there are guns with quite advanced looking stocks that still appear to have been touched off by hand and show no attempt at a the installation of even the simplest form of mechanical ignition system.

Nota Bene: I reserve the right to change my mind and re write this entire post as my research progresses and new data comes to light.

Acknowledgements

Terminology

The earliest known attempt at a mechanical lock

The earliest example of a Handtpuchse with any semblance of a lock mechanism that I know of comes from a German ''Büchsenmeisterbuch' (Master gunner's book) dating to 1411. This weapon consists of a simple Handtpuchse with a 'Z' shaped serpentine that passes through a slot in the stick-stock (either that or it is nailed to the left side) and swivels on a nail driven through the stock. Primitive though this may look it is a massive improvement on the earlier Handtpuchse where the shooter could either:

- Ignite the gun himself which distracted him from the task of aiming.

- Aim properly and enlist an assistant to ignite the gun.

|

Figure 1. A serpentine equipped Handtpuchse from a German 'Büchsenmeisterbuch' (Master gunner's book) dating to 1411. Note the way the serpentine appears to be mounted on the left side of (or pass through) the stick-stock and that the serpentine appears to hold a length of tinder rather than a slow-match. Source: Codex Germ. 3069 [click here] |

Strangely enough this remarkable upgrade to the normal stick-stocked Handtpuchse does not seem to have caught on all that much. Images from the 1480s and into the 1490s show large formations of hand gunners still using the old low-tech non mechanically ignited Handtpuchse. In fact Handtpuchsen remained in use in Europe well into the 16th century. One can only speculate about the reason why the serpentine equipped Handtpuchse did not catch on. Possibly this was because aiming instinctively and setting off a Handtpuchse with a match was not sufficiently difficult for a single hand gunner engaged in volley fire as to necessitate the use of a serpentine lever. However, once firearms emerged which had longer barrels and were capable of accurate shooting at longer ranges the accuracy of instinctive shooting was no longer enough to hit even a formation of oncoming soldiers at such ranges. Thus sighting along the barrel became necessary which in turn necessitated the use of a mechanical ignition system and a better stock.

|

Figure 2. A gaggle of hand gunners on the march from a German manuscript of the 1480s or 1490s (1482 by one estimate). None of them seem to have opted for the upgraded high-tech Handtpuchse from Codex Germ. 3069 since there isn't a serpentine lever in sight. Nor do have any of these Handtpuchsen exhibit a stock design more sophisticated than a simple stick. Unsophisticated though these things look they are easy to mass manufacture. Source: Haubuch Wolfegg [click here] |

|

Figure 3. An actual surviving Handtpuchse with a serpentine. The gun itself reportedly dates to the first half 15th century. Note the spring on the stick-stock. The serpentine and the hook were added at some time during the gun's service life which is likely to have been lengthy and there is no guarantee the modifications were done at the same time. Even so the modification likely dates to the 15th century. I am not sure if the barrel is copper alloy or iron but according to the source it had traces of red led base paint which usually indicates iron or mild steel. I cannot vouch for the authenticity of this gun but I have no reason to distrust the source of the images. Source: Michael Trömner, [click here] |

Stock designs

|

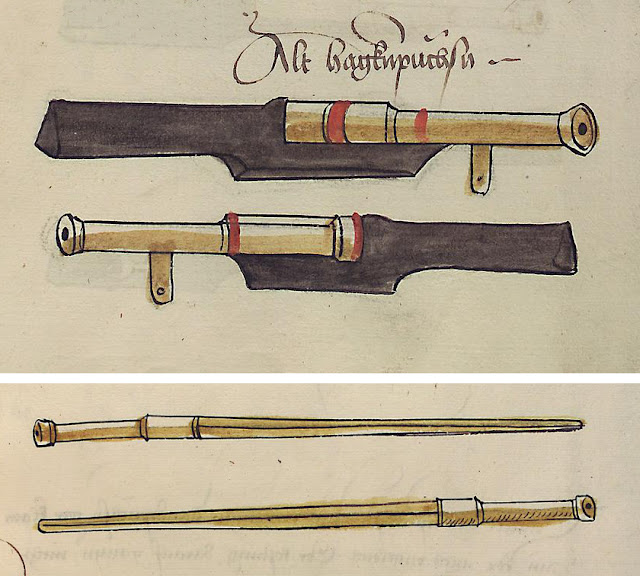

Figure 4. Guns the author of the Landshut armoury inventory deemed 'Alt Hagknpuchsen' (top) and 'Aeltere Handtpuchsen' (bottom), i.e. old hook-guns and hand-guns. Note the red bands on the barrel of the upper gun. These are probably iron barrel bands which were routinely painted in red led based paint for rust protection. This can be seen on iron components of artillery gun carriages and limbers. Source: Codex Pal. germ. 130 via the University of Heidelberg. |

|

Figure 5. These guns are simply labeled 'Hagknpuchsen' and are sometimes described as being intended for use in war wagons and presumably also for use from fortifications. Source: Codex Pal. germ. 130 via the University of Heidelberg. |

|

Figure 6. Method of firing a heavy Hagknpuchse from the Maximilanisches Zeugbuch. While the stock of this gun looks like that of man portable long arms modern people are used to it was more like a kind of wall gun or light artillery. It could be fired from a crenel, a firing slot in a wall or a war wagon or from a light folding tripod such as this one. It was a crew served weapon much like an anti-tank rifle of the WWI and WWII. Source: (BSB-Hss Cod.icon. 222) Münchener DigitalisierungsZentrum |

|

Figure 7. There were many of different stick-stock shapes for Handtpuchsen other than just a straight stick. This illumination from an Italian manuscript from between 1457-1468 shows no fewer than three different variations being used alongside crossbows. But Handtpuchsem barrels were not just attached to the stock by a socket at the breech. The barrel of a simple Handtpuchse (hand cannon) could also be inletted into the stock as the right hand illumination demonstrates. Source: (MS. Canon. Class. Lat. 81) Bodleian Library via Spiridonov |

|

Figure 8. A Halberd, Arkebuse and Hagknpuchse depicted together gives us a rough relative size comparison. A halberd was normally around 2,5-3 meters long by the beginning of the 16th century. Assuming 2,5 meters, which is consistent with contemporary engravings showing short halberds similar to this one, the smaller Arkebuse is about a 1,2 m long, the heavy Hagknpuchse is 1,8 meters long. The artist who created the Zeugbuch did not busy himself trying to get proportions right so this image should be taken with a grain of salt. A surviving Arkebuse of this type that survives in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nürnberg is a mere 78 cm long and the Hagknpuchse was likely closer to 2 meters. Source: (BSB-Hss Cod.icon. 222) Münchener DigitalisierungZentum |

Early mechanical matchlock designs

The snap matchlock

|

Figure 9. A snap matchlock in its simplest completely externally mounted form. Pushing the serpentine forward caused it to get hooked on the little metal tab just underneath the forward end of the serpentine. Once the tinder had been placed in the jaws of the serpentine the pan cover was swivelled out of the way by hand and the prominent round trigger button at the right hand end of the image was pressed. This pulled the serpentine retention tab into the stock, released the serpentine which was then plunged into the ignition pan by the sickle shaped serpentine actuation spring. Source: Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Russia |

The mechanically linked matchlock

|

Figure 10. An early mechanically linked matchlock of c.a.1515 with a slow-match fitted. The crossbow style trigger lever is directly mechanically linked to the serpentine. Any movement of the trigger lever results in a directly proportional rotational movement of the serpentine. Pulling the trigger lever half way back will result in the serpentine being rotated half way towards the ignition pan. Relaxing your grip on the trigger lever will return the serpentine to its normal resting place as far away form the ignition pan as possible. Even when compared to a flintlock of the Napoleonic wars this mechanism is simplicity itself. Source: Michael Trömner, [source] |

Lock, ... meet stock

|

Figure 11. This image is dated to the last third of the 15th century by the Bavarian National Library. However, judging by the armour and equipment of the men in the cart it may date to the very late 1470s or early 1480s. Note the archer who is wearing a helmet and elbow cops with besagews as well a skirt of 'Zaddeln' that are probably attached to a padded jack similar to the well known Stendal 'gambesons' show in the right hand image. All of this is armour that was decidedly out of fashion by the 1470s but was probably still in arsenal inventories and likely to have been issued to a lower ranking but valuable soldier like an archer as old-fashioned but still functional equipment. The soldier behind the driver is clearly holding an Arkebuse which clearly has a snapping matchlock judging by the shape of the serpentine. As such it is the earliest depiction of an Arkebuse that I have been able to find. Source: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (BSB Cgm 734) via Spiridonov |

|

Figure 12. This image from the Amtliche Berher Chronik is dated to between 1474 and 1483 shows two soldiers marching in column. This is one of the less ambiguous images from this manuscript and shows what appears to be a snapping matchlock mechanism. While not complete accurate it does throw some weight behind the dating of the above picture from BSB Cgm. 734.

Source: Amtliche Berner Cronik Vol. 3, via Burgerbibliothek Bern |

|

Figure 13. There seem to have been two methods of holding and firing these Arkebusen The two uppermost soldiers on the left standing behind the wagon and the one in the right hand image hold the Arkebuse by the grip and forestock and aim along the barrel but they rest the butt of the stock on top of the shoulder. This is one of the ways stick-stocked Handtpuchsen were fired. However, the soldier in the foreground in the left hand image wearing the pink hose and doublet seems to have picked up on what a modern shooter would consider the obvious way of holding this weapon. He holds it by the grip and the forestock, pulls it into his shoulder and aims along the barrel. None of these men are holding a match and there are no assistants in sight to touch the weapon off for them. These are most likely Arkebusen with mechanical snapping matchlocks. Source: Amtliche Berner Cronik Vol. 3, via Burgerbibliothek Bern |

Some examples of very early Arkebusen

|

Figure 14. Two surviving Arkebuses of c.a. 1500 that are very similar to the weapons seen in the Maximilianisches Zeugbuch (BSB-Hss Cod.icon. 222). The upper one is suitable for a right handed user is in the Hermitage Museum. It is 78 cm long and the caliber is 10,9 mm. The lower gun suitable for a left handed user is currently in the Hofjagd und Rüstkammer. Images from the late 15th and early 16th century seem to indicate that both left and right handed versions were fairly common so there is no reason to believe that this was a systemic effort to account for left handers but left handers must nevertheless have appreciated this. The serpentine of the gun in the Hofjagd und Rüstkammer is a modern replacement but the original would have been generally similar though possibly made of copper alloy. The hole in the butt of the stock is for a wooden pin on an arsenal rack. These guns were stored horizontally in a rack which had a pair of two pins for each gun. One pin went through the hole in the butt of the gun stock while the forestock of the gun rested on the second pin. Another hypothesis posits that the slow match was threaded through the hole in the stock. Source: Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Russia Source: Hofjagd und Rüstkammer in Vienna, Austria |

|

Figure 16. Speaking of accessories, we don't often get a look at the complete collection paraphernalia that came with one of these early Arkebusen but here, just for once, we have what looks like all of it. This includes a ramrod with numerous screw-in tips, of whom I don't know what even half of them do. Some that I do recognise include a cleaning patch holder, a worm for removing bullets, a bore scraper and a ramrod head. This kit doesn't look all that different from cleaning rods you can buy in any sporting goods store today although a number of the replaceable tips are obsolete. The ramrod was usually (though not always) stored under the barrel. The various screw-in tips were often kept in a compartment in the butt of the gun stock but this weapon does not appear to have one. Other important kit is the powder flask and the bullet mould at the centre right of the picture. Finally, notice that this seems to be a trigger button fired snapping matchlock with an internally mounted spring and all the components fixed to a lock plate which is an improvement over the external locks of the guns in Figure 9. Source: Unfortunately Unknown |

The early 16th century 'Kalashnikov'

|

Figure 17. A rack of Arkebusen from the armoury of Maximilian I. Note the ornateness of the barrels which are essentially miniaturised copper alloy cannon barrels. In the coming decades after some spectacular victories had been won on the battlefields of Europe either solely by firearms or to a large extent because off firearms, demand for these weapons grew any attempt at ornamentation on general issue man portable firearms vanished although the expense of ornate decorations was still lavished on artillery. Source: (BSB-Hss Cod.icon. 222) Münchener DigitalisierungsZentrum |

|

Figure 19. I don't have the time or the space to embark on an analysis of all the different gun manufacturing traditions of early 16th century Germany so a few examples of German Arkebusen from the 1530s will have to suffice. From the top:

These weapons have a cleaner and quicker to make stock than the earlier models (Figure 14) and barrels are at best minimally decorated. The uppermost two weapons in particular are extremely simple weapons that would have been very efficient and quick to produce and they do indeed seem to have been made in large quantities. The lower two guns both have mechanically linked matchlocks and exhibit the two trigger types that were to become the most common going into the 17th century, the modern trigger and the lever trigger. |

Mass production

|

Figure 20. Racks of Arkebusen from the 1530s at the Západocéske Musezeum Pilsen. By the 2nd quarter of the 16th century the writing was on the wall and these weapons were starting to be ordered by the case and the cart load by customers all over Europe from armament producers in Germany and Italy. Akebusen like like these who are very similar to those made the cities of southern Germany, particularly Nuremberg, dating to the 1530s, exist in museums as far afield as Romania. Source: Západocéske Musezeum Pilsen, via Michael Trömner, [source] |

Advantages

There are several obvious advantages of Arkebusen over longbows, crossbows and even Handtpuchsen and they are not always what people often think they are. The Arkebuse is capable of practical accuracy at longer ranges than a Handtpuchse for a variety of reasons starting with its longer barrel and better method of aiming. However, the Arkebuse is comfortably outranged by longbows and crossbows. The big war winning advantage of the matchlock Arkebuse is not its range advantage over longbows and crossbows. Both longbows and crossbows are longer ranged and more accurate than the arkebus. It is the fact that the Arkebuse delivers much more surplus projectile energy than the longbow and crossbow, enough projectile energy to penetrate full plate armour. Longbows and crossbows of the type used in medieval field battles delivered a kinetic projectile energy of around 160-200 joules. Some of the biggest crossbows of the era could deliver somewhat more kinetic projectile energy than this. However, the bow had to get quite large before it could deliver a projectile at something approaching the kinds of kinetic projectile energy levels that an Arkebuse could.

A huge lafette mounted crossbow that survives in the collection of Schloss Quedlinburg and dates to the early 14th century that has a 2,75 m long stock and originally had a composite prod some 3,5 meters long was capable of shooting javelin sized quarrels capable of delivering some 640 joules. To put that into perspective, this is how big a bow would have to get to deliver the same kinetic projectile energy as a modern 9mm Parabellum pistol round. To get a feeling for the relative power of a normal Arkebus of the early 16th century:

- An Arkebuse with a caliber of 15 mm fires a ball of about 20 grams. If it has a muzzle velocity of 300 m/s it will deliver a kinetic projectile energy of 900 joules. That is 28% more than the Quedlinburg ballista.

- Assuming a more anaemic 250 m/s for the above gun we still get 625 joules of kinetic projectile energy.

- A Schwere Arkebuse of 20 mm caliber (a 47,5 gram ball) with a muzzle velocity of 300 m/s will deliver a kinetic projectile energy of 2115 joules. This is about three times more kinetic energy than the Quedlinburg ballista could deliver and an order of magnitude more than a longbow.

Thus an Arkebuse of the 1530s with an anaemic powder load could deliver the same kinetic energy as the Quedlinburg ballista compressed into in a roughly 1 meter long man portable package weighing 4 kg that was capable of being fired by a single soldier. However, there is reason to believe that the muzzle velocity of these early Arkebuses was considerably higher than the conservative figures I gave above. Increase the muzzle velocity of the 15mm Arkebus to 400 m/s raises the kinetic projectile energy to 1600 joules. But kinetic energy is not the only factor at play here. The geometry and the material the projectile is made of also matters, as does the angle of impact. However, judging by the slaughter of the French heavy horse at Pavia, it seems that at ranges of at least 25-35 meters even these earliest Arkebuses were able to wound or even kill knights and barded horses whose armour could completely defeat longbow and crossbow projectiles at any range (siege crossbows and monstrosities like the Quedlinburg Ballista excepted). To quote a biography of Fernando Francesco d'Ávalos, marquis of Pescara, one of the commanders at Pavia, which seems to have been written within 25 years of the events:

"For this reason, Lannoy, being in trouble and only withstanding the fury of the royal [French] artillery with difficulty, Pescara who with marvellous prudence and always alert and prepared for all contingencies, immediately sent him help in in the form of about eight hundred Spanish arquebusiers who, pouring in from the rear and the flanks, unleashed a terrible storm of arquebus fire killing a great number of men and horses ... But the lightly armed Spanish soon withdrew back [to the shelter of the pikes?], and from there they mocked the fury of the [French] horse, steadily increasing in number, these were veterans trained in Pescara's new tactics. Without order they [the French cavalry] spread all over the field. It was a way of fighting that is longer used, ... many honoured captains and knights often, without being able to strike back, were shot down by ignoble foot soldiers ... It was a battle that was very dangerous and greatly disadvantageous to the French horse, because the Spanish who had surrounded them on all sides threw an endless fusillade of lead balls at them. These were discharged not from hand cannons [scoppietti] (as were used a short time ago) but by larger pieces, which are called harquebuses. Not just one man-at-arms but often two soldiers and two horses were shot through, so many that the countryside was covered by a miserable killing field of noble knights and horses, which died together ..."

Source: 'Le vite del Gran Capitano e del Marchese di Pescara' , P424-5. (Italian translation from the latin of 'Vitae illustrium virorum' by Paolo Giovio, 1551)

My Italian sucks but this is in line with other translations of this text that I have seen. Pavia must have been a major game changer both technologically and tactically simply because of the shock value of so many nobles in full plate being unceremoniously gunned down. It seems that even early Arkebusen could simply put a such a superabundance of kinetic energy behind a lead ball that it could achieve armour penetration despite its shortcomings as an armour piercing projectile at ranges where arrows and quarrels could not. Of course armourers responded by thickening armour, making it of better steel and for the high end customers, heat treating it, which led to a fierce arms race between armourers and gunsmiths.

During the course of the 16th century the Arkebuse would grow in size, calibre and barrel length until by the Thirty Years War it had grown to be around 1,6 meters long, sported a caliber of around 20 mm and was so heavy it could not be easily fired without a forked monopod to rest the barrel on. These are the same basic specs as the Schwere Arkebuse in Figure 19.3. The wall gun of the early 16th century had become the general issue musket of the 17th century. The ease and economy of manufacture of the matchlock gun has been discussed above. This factor contributed to keeping matchlocks in military service long after more advanced self igniting lock mechanisms had been developed. As militaries moved into the 18th century and better steel became available the calibre of long arms went down and muzzle velocity went up which made the weapon more portable again.

Disadvantages

Cheap and powerful a weapon though it was the matchlock had some glaring shortcomings. First among them was the match. In rainy or damp conditions the matches were hard to keep lit. Matches also gave away the position of pickets and guards, if not by the light of the glowing match, then by the smell of it. Furthermore, in order to be ready to fire at all times, the match had to be kept constantly lit. However, if every match of every Arkebusier in an army was kept lit at all times they would have burned through enormous amounts of slow-match. To economise on slow-matches it was common practice to have only part of a force, every 10th man in a column perhaps, carry a lit match. This cut down on slow-match consumption but it made it almost impossible for Arkebusiers to react quickly if they were caught by surprise by cavalry in a vulnerable state such as during a march. Arkebusiers needed the protection of pikemen under such circumstances while the time consuming process of lighting everybody's match was completed. Normally special troops were kept on strength whose only role was to run from soldier to soldier with a lantern for this purpose. The lit match also constituted a safety hazard. It was not unknown for Arkebusers to lose track of the glowing match in the heat of battle, bring it too close to a powder flask and blowing themselves or one of their comrades up.

Conclusion

Even though it has been neglected by historians and dismissed as primitive, the matchlock nevertheless changed history. It made the one-man portable firearm a truly practical weapon that, given the protection of pikemen, could make cavalry charges on infantry formations a very costly affair. Similarly small forces of entrenched Arkebusiers backed up by melee troops could see off massive frontal attacks by forces made of pure melee troops with very few losses to themselves as the battle of Battle of Bicocca demonstrates.

The matchlock was quickly perfected to be easy and efficient to produce. By the 1530s all ornamentation on mass made military issue matchlocks had been stripped away. Copper alloy barrels were giving way to iron and steel barrels and locks were being made as consistently shaped and in standard(ish) sized units for ease, speed and economy of assembly. The Arkebuse compressed penetration power previously only to be found in very large crossbows and ballistas into a man portable weapon that at ranges of at least 25-35 meters could pierce late 15th and early 16th century plate armour which was proof against crossbow and longbow projectiles. This led to the thickening of armour and the constant enlargement of the Arkebuse until it had morphed into the familiar unwieldy musket of the 30 years war. The musket eventually more or less won the guns vs. armour race in that all infantry and most cavalry had shed their armour by the 18th century except for specialist heavy shock cavalry that retained breastplates and helmets.

The matchlock has outlasted a long line of technologies that took a stab at consigning it to oblivion. This includes the snaplock, snaphaunce, miquelet, doglock and the flintlock, wheellock, the percussion lock and a whole plethora of paper and metal breech loader cartridge technologies. Matchlocks were still in use in remote areas of the world until quite recently in a world of centre fire cartridge fed assault rifles and high performance hunting rifles. That is quite an achievement.

(1)The siege of Plevna demonstrated spectacularly the superiority of repeating rifles over the single shot military breechloader causing a mad scramble all over Europe to arm militaries with magazine fed repeating rifles